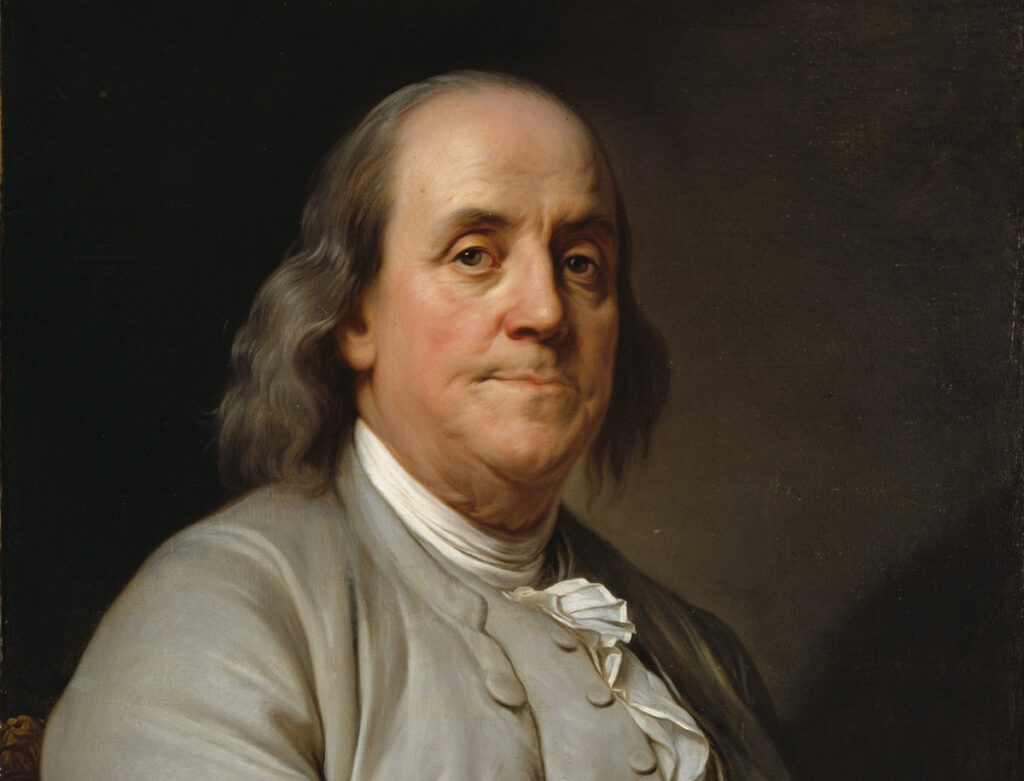

Benjamin Franklin was a prodigious inventor. He created devices to fulfill a need or desire. We find nothing strange about this today, it is a classic description of how the marketplace operates.

We forget that in Europe, before and during colonial times, there was an upper class and commoners. The upper class was made of owners who made the rules, the commoners were workers who obeyed the rules. If there was a need to be fulfilled the ruling class made that decision. Commoners stayed desperately poor.

The wilderness of America changed this hierarchy. Settlers, mostly commoners, learned that if they wanted something done they had better do it themselves. Mere farmers became masters of many trades. They didn’t wait for anyone’s permission.

As the population of the colonies grew, the marketplace grew. Small businesses began to pop up offering goods and services. Franklin printed a newspaper. He also formed “The Leather Apron Club,” later called the “Junto.” Its purpose was to encourage entrepreneurship and improve society. People with dirt under their fingernails were proposing libraries, fire departments, hospitals, and even universities. It was the beginning of the middle class.

Customers, husbanding their hard-earned cash, forced producers to compete to provide value. Waste was curtailed, demand increased, more products were sold. Without government intervention, the colonies were becoming prosperous. Goods common people desired could be obtained, while in Europe, commoners could only desire.

Modern economists often highlight competition’s value to the marketplace. Quality systems, such as Toyota’s, seek to eliminate “all waste.” Franklin realized that competition and waste were connected. Like opposite ends of a seesaw, when one goes up the other goes down and vice versa. Competition eliminating waste across the breadth of society is the engine of prosperity.

Waste is a pernicious thing. To paraphrase Franklin, “struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive.” One would think if you eliminated waste today, you could forget about it tomorrow. Unfortunately, the world doesn’t work that way.

The marketplace is mechanical, nothing happens magically. It is up to human curiosity, sweat, toil, and tears to discover what works, why it works, and how to keep it working. Every day, throughout the marketplace, a great deal of effort is expended managing waste. There is a self-policing penalty for doing careless and foolish things. If a company doesn’t get the details right, it goes away.

Government is philosophical. The “Statutes, Acts, Edicts and Placaarts of Parliaments” are necessarily broad as they apply to an entire nation. They are “best guess” efforts of officials to run a country. Bureaucracies are not designed to handle the tiny details and issues that arise in the marketplace daily. Imagine the government managing the individual problems of America’s 32 million small businesses. It is simply impossible.

In colonial times, England’s philosophy gave aristocrats the power to run things. There was no competition and the resulting waste kept England a static two-class system. Without middle-class competition, the marketplace could not create prosperity. The inevitable result was widespread poverty.

In 1867, Karl Marx made a guess that was stupendously wrong. His philosophy, known as socialism, argued that prosperity would result if the government controlled the factories and tools necessary to make goods and services. Wherever it was tried, government became lost in the details. The prosperity promised gave way to abject poverty. A middle class never emerged.

Today our leaders are obsessed with the philosophy of “global warming.” They have decided that government should force the marketplace to become “sustainable.” There appears to be no understanding or concern for the millions of tiny details that mechanical reality insists must be addressed.

By now we should be able to predict what will happen.

Government demands will distort the marketplace. The sheer number of details will mean many are neglected. The resulting waste will cause more waste, economic output will diminish and the middle class will begin to shrink, until it disappears.

It doesn’t matter what name a government is given, socialist, fascist, despotic, or democratic. When government runs the marketplace, the eventual result is a small upper class, a massive lower class, and poverty.

“Beware of little expenses, a small leak will sink a great ship,” so said Poor Richard, a Franklin alter-ego. Franklin realized that the best way to stop leaks was for the masses, commoners if you will, to share in economic advancement. Their own self-interest would spur the competition necessary to eliminate waste.

“Perhaps, in general;” he wrote, “it would be better if Government meddled no further with Trade, than to protect it, and let it take its course.” Franklin, the prodigious inventor, knew that was how to create a middle class, the engine of prosperity.